In October 2020, I had discovered to lumps on Porter. One on his chest and one alongside of his penis. Porter was taken to his primary veterinarian, who did a fine needle aspirate of both growths. It was determined at that time that both masses were mast cell tumors and had to be removed.

On October 13, 2020 Porter had both tumors surgically removed. On October 21 the pathology report was completed. We were extremely relieved that both tumors were a grade 2, (which is still considered to be low-grade and not life threatening at this point). Our amazing vet, Dr. Campbell at Old York Veterinary Hospital was able to get clean margins during surgery as well.

Some of the typical treatments to prevent possible future mast cell tumors are not an option for Porter. He was started on a daily low dose of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication to help decrease the risk of new mast cell growth. However, as more epilepsy medication was necessary, we had to eventually stop the anti-inflammatory medication in order to address the more concerning immediate diseases.

| The following information was written by: Christopher Pinard, DVM; Robin Downing, DVM, DAAPM, DACVSMR, CVPPDVM and reposted from VCA Animal Hospital : |

What is a Mast Cell Tumor?

What is a mast cell?

A mast cell is a type of white blood cell that is found in many tissues of the body. Mast cells are allergy cells and play a role in the allergic response. When exposed to allergens (substances that stimulate allergies), mast cells release chemicals and compounds, a process called degranulation. One of these compounds is histamine. Histamine is most commonly known for causing itchiness, sneezing, and runny eyes and nose – the common symptoms of allergies. But when histamine (and the other compounds) are released in excessive amounts (with mass degranulation), they can cause full-body effects, including anaphylaxis, a serious, life-threatening allergic reaction.

(Image via Wikimedia Commons / Joel Mills (CC BY-SA 3.0.)

What is a mast cell tumor?

A mast cell tumor (MCT) is a type of tumor consisting of mast cells. Mast cell tumors most commonly form nodules or masses in the skin, they can also affect other areas of the body, including the spleen, liver, intestine, and bone marrow. Mast cell tumors (MCT) are the most common skin. Most dogs with MCT (60-70%) only develop one tumor.

What causes this cancer?

Why a particular dog may develop this, or any cancer, is not straightforward. Very few cancers have a single known cause. Most seem to be caused by a complex mix of risk factors, some environmental and some genetic or hereditary. There are several genetic mutations that are known to be involved in the development of MCTs. One well-known mutation is to a protein called KIT that is involved in the replication and division of cells.

While any breed of dog can get MCT, certain breeds are more susceptible. MCTs are particularly common in Boxers, Bull Terriers, Boston Terriers, and Labrador Retrievers.

What are the signs that my dog may have a mast cell tumor?

Mast cell tumors of the skin can occur anywhere on the body and vary in appearance. They can be a raised lump or bump on or just under the skin, and may be red, ulcerated, or swollen. While some may be present for many months without growing much, others can appear suddenly and grow very quickly. Sometimes they can suddenly grow quickly after months of no change. They may appear to fluctuate in size, getting larger or smaller even on a daily basis. This can occur spontaneously or with agitation of the tumor, which causes degranulation and subsequent swelling of the surrounding tissue.

When mast cell degranulation occurs, some chemicals and compounds can go into the bloodstream and cause problems elsewhere. Ulcers may form in the stomach or intestines, and cause vomiting, loss of appetite, lethargy, and melena (black, tarry stools that are associated with bleeding). Less commonly, these chemicals and compounds can cause anaphylaxis, a serious, life-threatening allergic reaction. Although very uncommon, MCTs of the skin can spread to the internal organs, causing enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, and liver, sometimes with fluid build-up (peritoneal effusion) in the abdomen, causing the belly to appear rounded or swollen.

How is this cancer diagnosed?

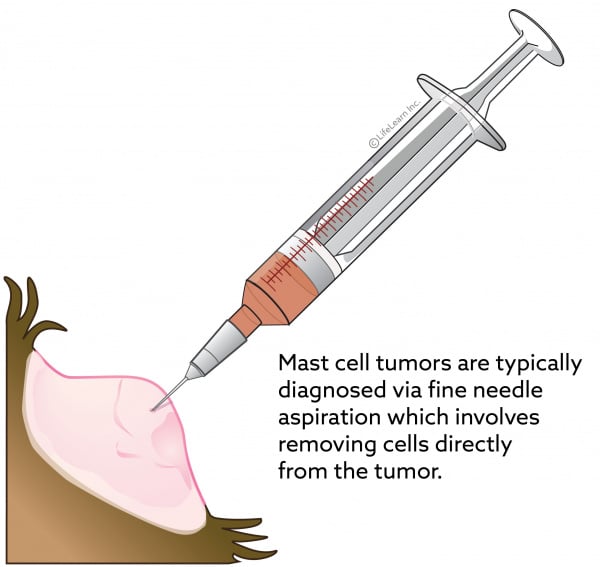

This cancer is typically diagnosed via fine needle aspiration (FNA). FNA involves taking a small needle with a syringe and suctioning a sample of cells directly from the tumor and placing them on a microscope slide. A veterinary pathologist then examines the slide under a microscope. In cases where the aggressiveness of the tumor is essential to best management,a surgical tissue sample (biopsy) can be beneficial; this is particularly true for MCTs.

MCTs have been classically called ‘the great pretenders’ in that they may mimic or resemble something as simple as an insect bite, wart, or allergic reaction, to other, less serious, types of skin tumors. Therefore, any abnormalities of the skin that you notice should be evaluated by a veterinarian.

Once a diagnosis of MCT has been made, your veterinarian or veterinary oncologist (cancer specialist) may recommend performing a prognostic panel on a tissue sample. This panel provides information on the genetic makeup and abnormalities of the tumor and provides valuable information that your veterinarian will use to determine the prognosis (the likely course of the disease) for your dog.

How does this cancer typically progress?

This tumor’s behavior is complex and depends on many factors. Typically, when the tumor cells are examined under a microscope, the pathologist can assess how aggressive the cancer is based on several criteria. The tumor as a whole is graded from I-III, with grade I as much less aggressive than grade III MCTs. Higher grade tumors have a higher tendency to metastasize (spread to other parts of the body).

Typically, the prognosis is less favorable if:

- the patient is one of the susceptible breeds

- the MCT is located at a junction where the skin meets mucous membranes (e.g., the gums)

- when viewed under the microscope, the number of cells actively replicating is high

What are the treatments for this type of tumor?

Despite the range in behavior and prognoses, MCTs are actually one of the most treatable types of cancer. The higher-grade tumors can be more difficult to treat but the lower-grade tumors are relatively simple to treat. In cases of any MCT diagnosis, looking for spread of the cancer to other areas in the body is usually advised. This is important, as it helps your veterinarian develop the best treatment options for your dog.

In lower-grade tumors with no evidence of spread, surgery is likely the best option. Surgery alone for lower-grade tumors provides the best long-term control, and chemotherapy is not typically required. However, in higher-grade tumors, even without evidence of spread, a combination of surgery and chemotherapy is often recommended. Radiation therapy is another option if the mass is not in a suitable location for surgical removal or if the surgical removal is incomplete (with cancerous cells left behind). Discuss treatment methods with your veterinarian and veterinary oncologist.

Given that we now know there is an underlying genetic basis for MCT, drugs are being designed to specifically target the proteins associated with the development of cancer. In patients with non-surgical MCT, or recurrent MCT that has failed to respond to other chemotherapies, targeted therapy becomes a much more appealing option.

Is there anything else I should know?

Given how reactive MCT is, with degranulation easily triggered with pressure, you should avoid palpating (feeling) or manipulating the tumor. As well, your dog should not be allowed to chew, lick, or scratch it, as this may also trigger degranulation. Degranulation may lead to further itchiness, swelling, and discomfort, or even bleeding. Your veterinarian may recommend the use of an Elizabethan collar (E-collar or cone).